Music for Mondrian

I feel absolutely privileged and not undaunted to be invited by the National Gallery of Ireland to respond to this landmark Mondrian exhibition. It’s the first-ever exhibition of work by this Dutch master and pioneer of 20th-century abstract art and represents the culmination of years of collaboration and planning with the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, which has the largest collection of Mondrian works in the world, The Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland. All but two artworks are on loan from the Kunstmuseum.

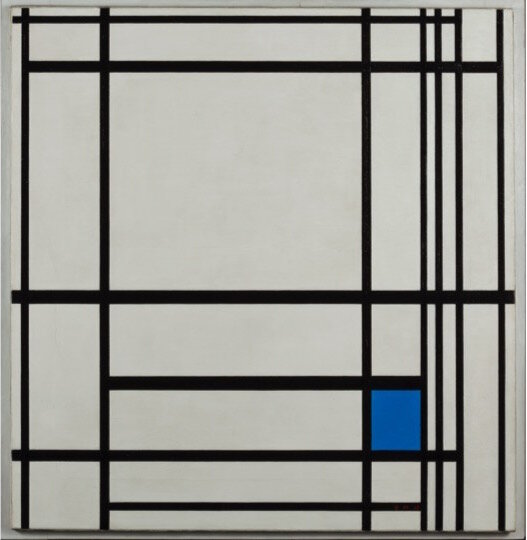

Piet Mondrian’s name is synonymous with Modernisn - it practically rhymes with the word. The 40 paintings by Mondrian in this exhibition follow his artistic progress from early landscapes to his world-renowned abstract works with their black and white grids and primary colours.

I’ve been asked to produce a podcast, a musical response and also to contribute on one of the National Gallery\s Talk & Tea events. Since there’s such a vast amount of material available, I’ve decided to dedicate a page here to my research. These are my notes and explorations and what I’m finding fascinating and illuminating!

These notes also accompany the playlist Music for Mondrian on Spotify. There a lot more tunes on the list than I cover here, the reasons being that sometimes I found interesting versions of the same tune or additional tunes or composers gives a broader sense of the musical history of the time. Anyway, I hope you enjoy it!

And listen to an interview with National Gallery Director Sean Rainsford on soundcloud here

Read an interview with curator Janet McLean here

See video by the Irish Times

Read Out of the Darkness and into the Ligh by Una Mullaly, Irish Times, Dec 22

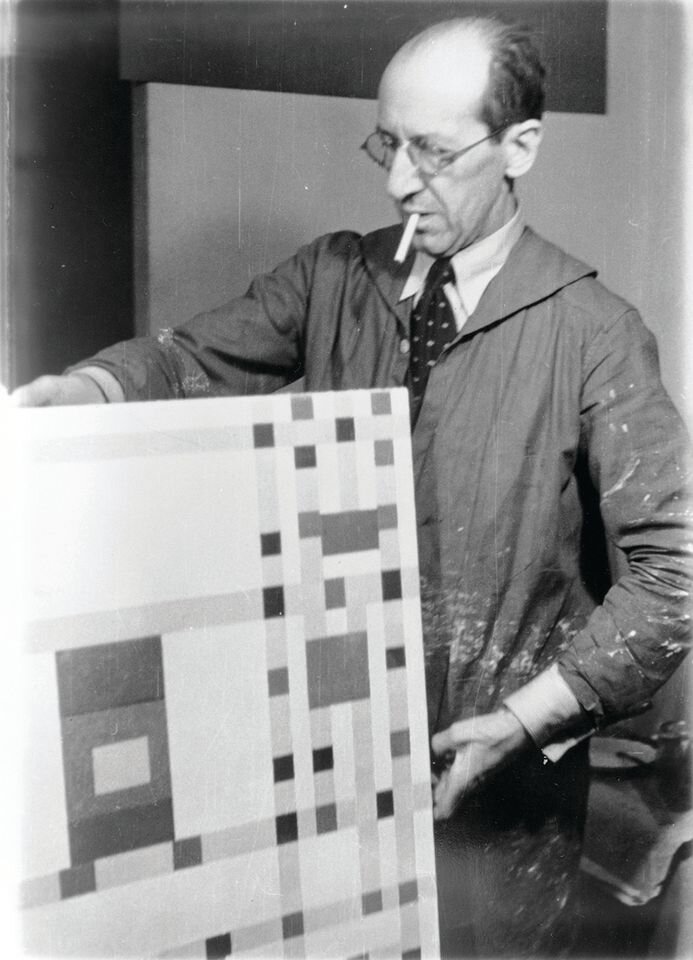

Piet Mondrian with Broadway Boogie Woogie, New York, 1943. Photo by Fritz Glarner. Courtesy the Collection RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History.

References:

A selection of books, websites and references which have informed my work:

Holtzman, Harry and James, Martin S., et al editors, The New Art - The New Life, The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian.

Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag, Piet Mondrian - The Man Who Changed Everything.

Golding, John, Paths to the Absolute.

Ross, Alex, The Rest is Noise

Holtzman, Harry & Madalena, et al., (Edited by Wietse Coppes), 3 INTERVIEWS: Thelonious Monk / T.S. Monk

Selection from Archives of www.newyorker.com:

A Visit to Mondrianʼs Grave By David Kortava February 25, 2019

Does “Late Style” Exist?

Shapes of Things | The New Yorker

Selection from The New York Times Archives:

ART REVIEW; The Joy, Jazz And Delicacy Under Those Mondrian Grids Sept. 29, 1995Harry Holtzman, Artist, Dies; An Expert on Piet Mondrian - The New York Times

Mondrian’s World/ From Primary Colors to the Boogie Woogie - The New York Times

Mondrian and his Studios – Exhibition at Tate Liverpool | Tate

Selection from The Guardian Archives

Piet Mondrian review – studio soirees and all that jazz | Culture | The Guardian

Piet Mondrian review – studio soirees and all that jazz | Culture | The Guardian

The Tate Gallery

MOMA

Wikipedia

Music for Mondrian Timeline

Mondrian was born in Holland, 1872 in Amersfoort. Hi father was a school principal and by all accounts, Mnndrian had a strict Protestant upbringing. He qualified as a teacher before going back to study art at the Rijksakademie. From 1893 he supported himself as an artist, painting still lifs, landscapes and portraits, copies from the Rijkemuseum and giving private lessons.

The Royal Wax Candle Factory

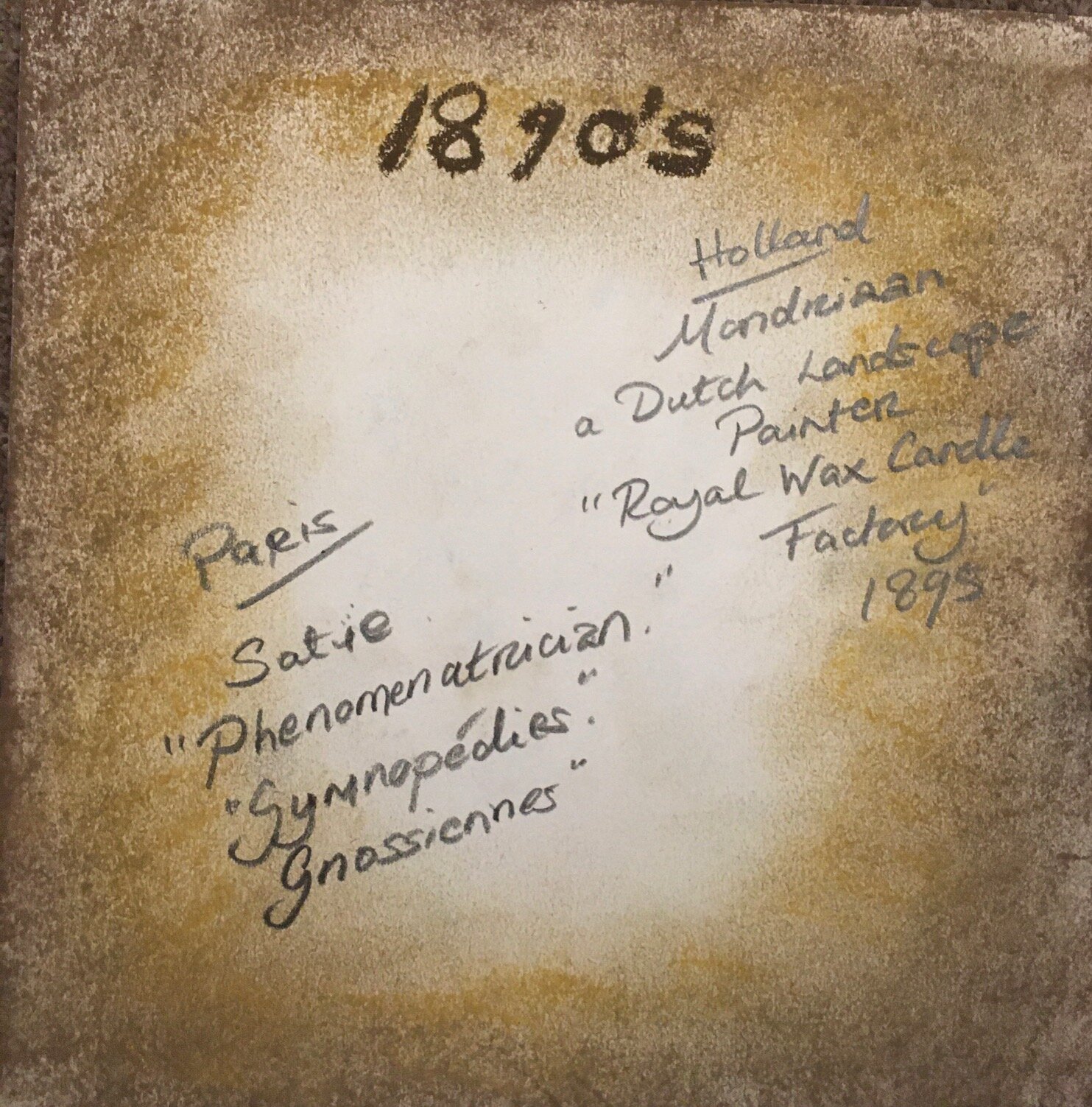

1890’s Premonitions of things to come

LISTEN: Satie: Grossiennes - Noriko Ogawa

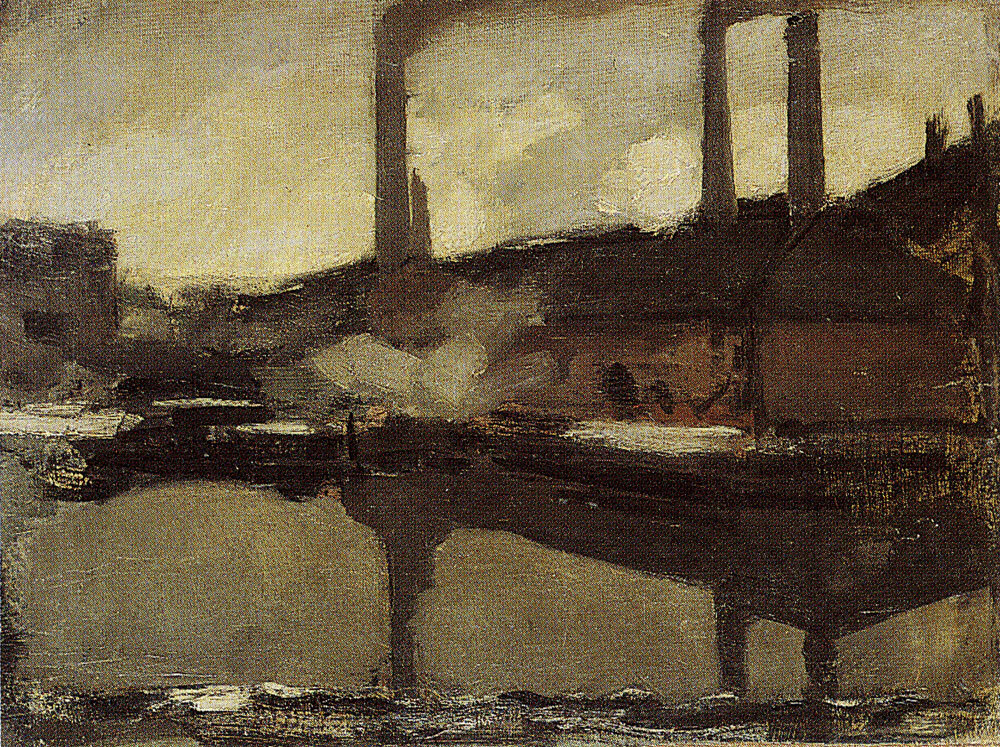

In the 1890s Mondrian was producing paintings pretty much consistent with Dutch tradition in style, subject matter and form. The earliest Mondrian painting in the National Gallery exhibition dates from 1895 and is a small study of the Royal Wax Candle Factory in Amsterdam. A premonition of his later work is detectable in how he blocks in colour and the dominating use of horizontals and verticals to divide the space. Set at the edge of the Boerenwetering canal, the blackened chimneys make a grid-like reflection on the grey water. These premonitions are evident throughout his early work but to all intents and purposes, they are there unconsciously.

In contrast, if we go over to Paris 1890s, we encounter a singular chap, one Eric Satie, 6 years Mondrian’s senior. Neither he nor his music was consistent with dominant Parisian musical trends. Eschewing the traditional view of composer, he instead wanted to be known simply as a phonometrician, one who works with and measures sound. He was against all the excess, exaggeration, ornamentation and melodrama either in composition or performance so typical of romanticism. For him, it obscured the music. He was in fact an early exponent of Joycean “scrupulous meanness” His compositions are brief and often quite stark, almost like aphoristic statements of his harmonic and rhythmic explorations. Satie did not think a composer should take more time from his public than strictly necessary. And he diverged from the romantics in the august titles he gave his work: often names entirely of his own invention. is still a degree of head scratching as to the origin and exact meaning of titles like Gnossiennes and Gymnopedie, Gnossiennes seems to be a word entirely created by Satie and his manuscript contained no bar lines or time signature. Needless to say, La Belle Epoque Paris did not welcome his unadorned and divergent approach.

LISTEN: Stravinsky: The Firebird, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer

LISTEN: Schoenberg: 3 Piano Pieces, Opus 11: No. 3, Daniel Barenboim, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra

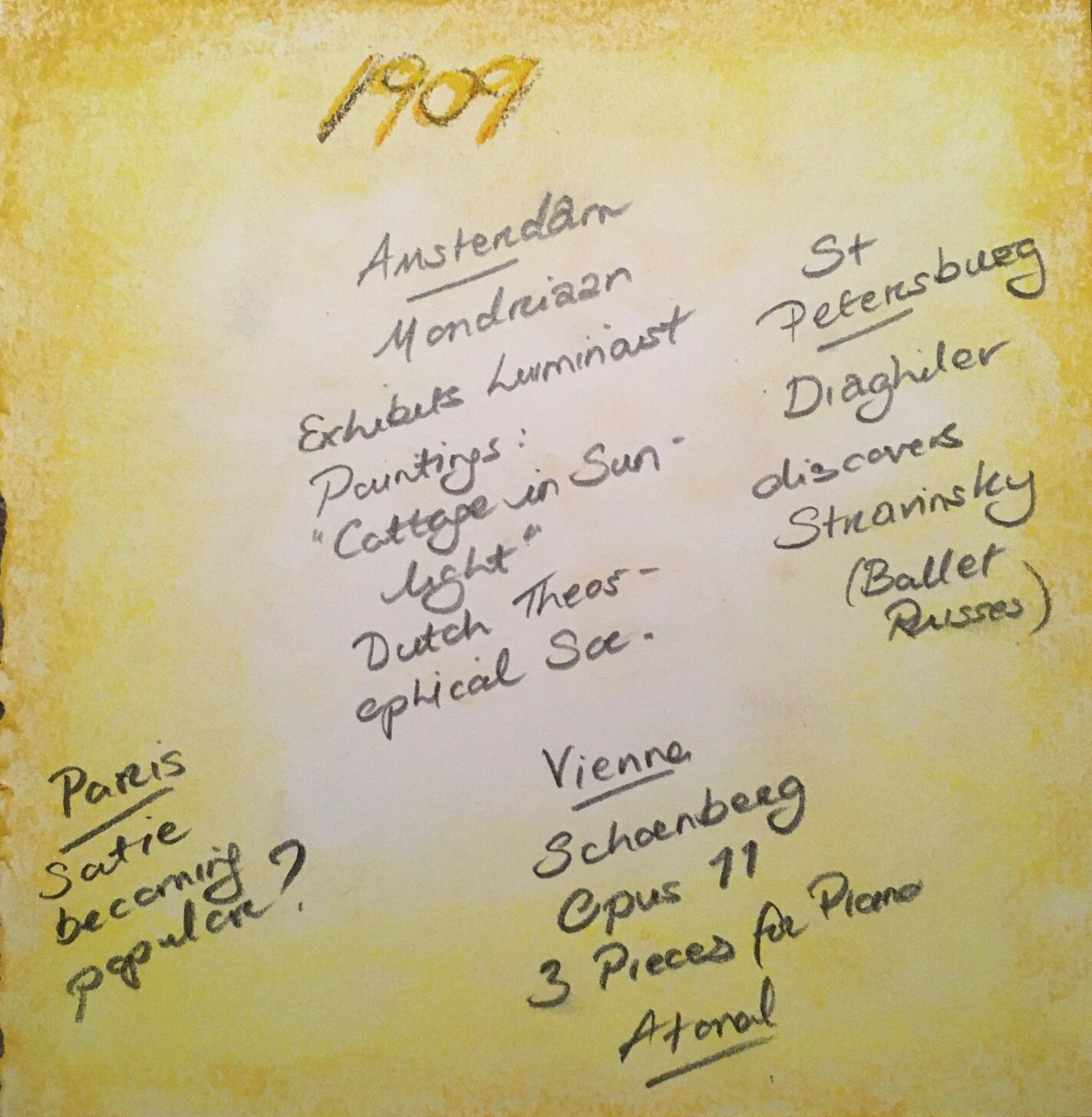

2. 1909: House in Sunlight, Satie, Schoenberg, Stravinsky

Something that began to fascinate me in my research was the simultaneity and synchronicity of events. The first example of this comes in 1909 which turns out to be a pivotal year musically and artistically.

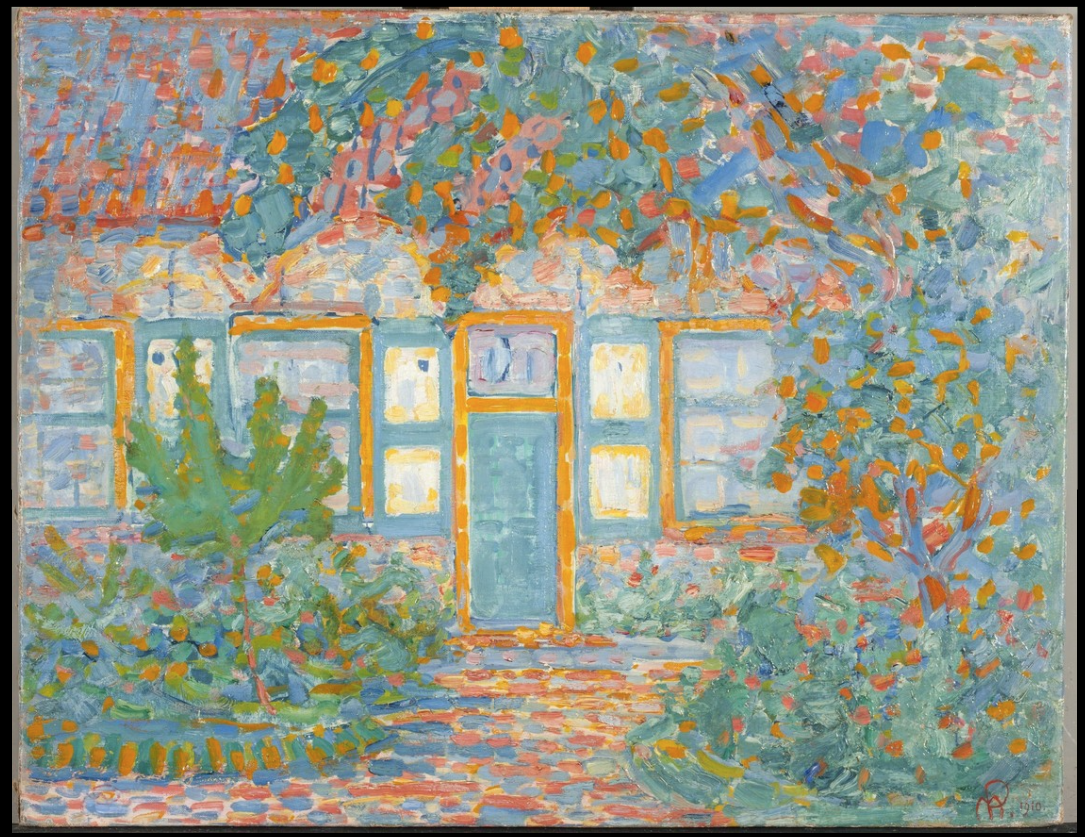

Mondrian exhibited his Luminist paintings at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. These paintings, such as House in Sunlight were quite a departure from previous work with the use of much brighter colours in a pointillist style. In departing from the Dutch styles around him, Mondrian showed himself to be the most controversial artist of the exhibition.

Mondrian, House in Sunlight, 1909 Courtesy Kunstmuseum Den Haag

This same year he joined the Dutch Theosophical Society, having been interested in the spiritual movement for some time. Rather than attempt to sum up this spiritual movement led by Madame Blavatsky and do it an injustice, I think I’ll leave it to our own Yeats, also a member of the group to convey it poetically:

Between extremities

Man runs his course

A brand or flaming breath

Comes to destroy

All those antinomies of day and night

The body calls it death

The heart remorse

But if this be true, what is joy?

A tree there is that from its topmost bough

Is half all glittering flame and half all green

Abounding foliage moistened with the dew;

And half is half and yet is all the scene

And half and half consume what they renew,

In The Rest is Noise, Alex Ross posits that it was the sense of possibility and vitality of the turn of the century, the restlessness to break with old classical forms and beliefs that accounted for and led many, particularly artists, to spiritual seeking, theosophy, Swedenborgism, Kabalism, Rosicrucianism, neopaganism, political communism, anarchism and ultranationalism. Satie too was a member of the Rosicrucian order who were very linked with symbolism.

1909 was also the year that Stravinsky was discovered! Diaghilev attended the performance of Feu d’Artifice in St. Petersburg and was charmed. He brought dancers Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova and Ida Rubenstein, from the Imperial Theatre in Saint Petersburg to the Châtelet Theatre in Paris to found the infamous Ballet Russes. Included on my playlist are some excerpts from the first ballet Stravinsky wrote in Paris, in 1910, the mesmerising Firebird.

Another artist who also joined the Theosophical Society in 1909 was Kandinsky. Already sensitive to the connection between music and art and he wrote of the possibility of ”a new realm in which musical experiences is a matter not of sound but of soul alone. From this point begins the music of the future.”

In Vienna, Architect Loss manifested his attack on art nouveau’s compulsion to cover everyda objects in wasteful ornament by beginning construction on the Looshaus. Looshaus would turn out to be a modern building shocking Fin de Siecle Vienna.

Also in Vienna, Schoenberg was working on the similar quest to Satie albeit going a little further. He wanted to purify music of ornamentation and the inherited meaning of tonality and to create a new music in which the absolute logic of composition would become pure expression.

Schoenberg’s Opus 11, 3 Pieces for Piano, No. 3., composed in 1909 dispensed entirely with the tonal means of organisation and in abandoning the use of a tonal centre Schoenberg dissolved the structures from which western music had derived its sense of shape and order for 400 years. This piece sounded the emancipation of dissonance as it freed music from the convention of resolving dissonance!

Around this same time, the establishment who had so averted its gaze from Satie”s ungainly antics, might have been turning a slightly less disapproving glance his direction. The "Jeunes Ravêlites", a group of young musicians who followed Ravel, proclaimed their preference for Satie's earlier work reinforcing the idea that Satie had in fact been a precursor of Debussy. He could surely have done with the money, but it wasn’t in his nature to court populism, and with not much more than a shrug of his shoulders, Satie carried on his quaint path with his own eccentric explorations.

It is an interesting response on Satie’s behalf I think. By contrast, artists like Picasso and Dali had begun to grasp the concept of fame and that cultivating a persona might serve their ego as well as their advance their work. But for artists like Satie and indeed Mondrian, this was not interesting and could only be an irritating distraction.

Unintentional revolutionaries

Indeed for all of the artists I discuss here, Schoenberg, Satie and Mondrian they shared a similar attitude to the revolutionary aspect of their work. They viewed it very humbly and unremarkably as “the next logical step.”

Schoenberg saw his dissolving of tonal structures, their freedom from key and convention of resolving dissonance as the next logical step in harmonic development. He wrote, “I am conscious of having broken through all the fetters of a bygone aesthetics.” Mondrian too would see his Neo Plasticism as the next logical step from Cubism…

But in 1909, Mondrian had yet to take this “next logical step.”….. which he realised when he attended an exhibition in 1910 showing works by Picasso and Braque.

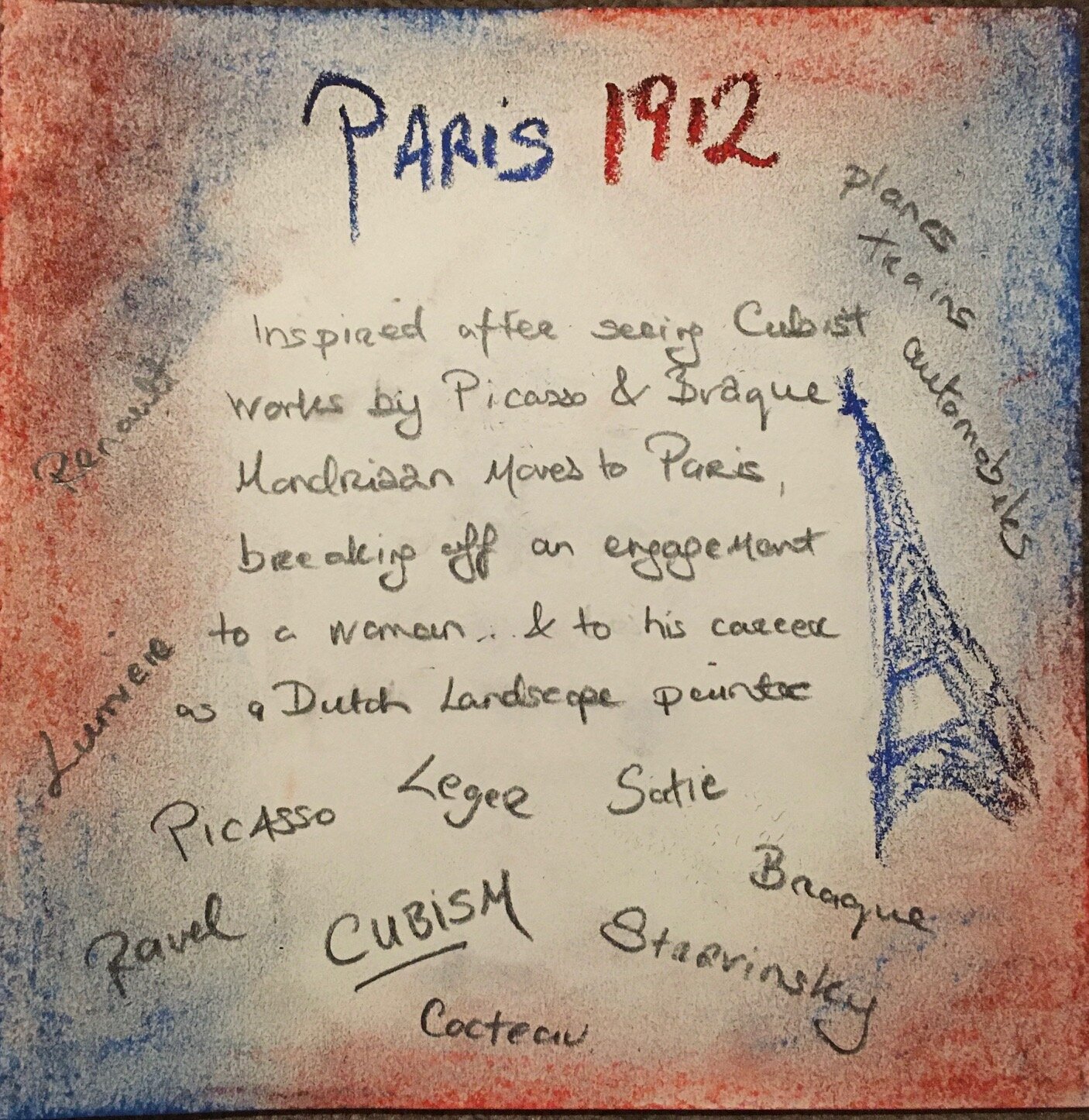

3. PARIS 1912 Taking the Next Logical Step!

Breaking off an engagement and abandoning a comfortable position as a fairly well respected Dutch landscape painter, in December 1911, Mondriaan moved to Paris. He arrived before Christmas at the very peak of the Belle Epoque.

Paris was a city at fever pitch of intellectual and artistic innovation, invention and experimentation. Driven dizzy by all the hope and high-mindedness of the new century, with glimpses of invincibility, Icarus was flying close to the sun, before spinning into the disillusionment and destruction that would come with the World War 1.

But in 1911, all was well and Mondrian was coming for his art. To be in the energy and activity of the cubists. And this decision, though he would barely spend 3 years in Paris, proved transformative for his work. We would probably never know of Mondrian had he not taken this risk. I was lucky to catch the exhibition at the National Gallery just before another lockdown closed it on Christmas Eve. The exhibit beautifully shows how Mondriaan’s work leaps forward to engage and integrate the exciting new style of Cubism even as it shows the artist finding his own way in the new language. In a similar way in which Schoenberg picked his way through traditional harmony to the dissolution of tonality, Mondrian’s Tree Compositions trace a similar path through a gradual complete dissolution of the figurative towards pure abstraction. But Mondrian does cubism Mondrian’s way. Typical Cubist subjects were the still life or the human form. But, Mondrian explores the style through a study pf nature and the man’s new nature, the city. In contrast to the Cubists too, his compositions show no attempt to describe volume. His trees are flat and void of natural dimensions, thereby erasing any trace of natural form. Also at this time he starts to removing any trace of narrative from the titles of his work calling them compositions.,

Mondrian descends from the cubists, but does not imitate them,” wrote critic and poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1913. “His personality remains entirely his own.”

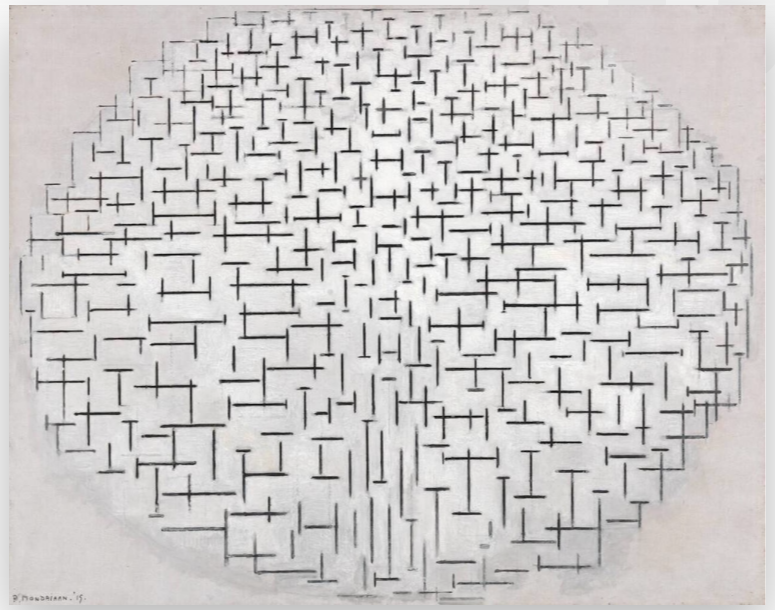

Piet Mondrian Composition of trees 2, 1912-13. Courtesy of Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Piet Mondrian Composition in Oval with Color Planes 2 1914. Courtesy Kunstmuseum den Haag

LISTEN: Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer

The Paris 1913 season opens with a scandal: Sacre! The Rite of Spring, Le Sacre de Printemps, ballet with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, music by Stravinsky, Nijinsky’s most adventurous and daring choreography and equally daring stage designs and costumes by Nicholas Roerich. Shouts from the audience, in praise and protest, during the performance were so loud, the dancers could not hear the music and Nijinsky hid in the wings, calling out steps. Ultimately though this “scandale” became a Succé de Scandale. Its affront of tradition, musical, dance and theatre paid off! Stravinsky’s score transformed how composers thought about rhythmic structure and harmony. Nijinsky’s choreography with its dominant parallel positions and not one ballerina en pointe shocked the ballet world, challenging cannon on classical ballet. This bombardment of the New, I would say, did indeed open the floor to modern dance and Parisian ears to the later sounds of jazz.

Given this musical earthquake, it is interesting, to me anyway, to learn that it is only when he comes to Paris, that Mondrian’s ears open to music. Prior to that, I find no evidence. Although, to be fair, I find very little evidence of there being a musical scene in Holland in the early 20th century, or at least, comparable to its art scene, or the music scene of Paris or Vienna. So by all accounts it is only in his 40s, and in Paris, that Mondrian shows any interest in music. He struck up a friendship with pianist-composer Jakob Van Domselaer who travelled to Paris to meet Mondrian in 1912.

Van Domselaer was fascinated by the emerging horizontal, vertical duality in Mondrian’s work which and its increasing abstraction. Inspired by Mondrian’s plus/minus compositions particularly, he composed Stijlproeven / Experiments in Style for Piano. I think it is very interesting to listen to Stijlproeven 1 in the playlist while looking at Mondrian's Composition 10 in Black and White, also named Pier and Ocean,

Composition 10 in Black and White, also named Pier and Ocean,

LISTEN: Van Domselaer: Proeven Van Stijlkunst I - IX, Kees Wieringa

Symbolically and inline with some of the spiritual teachings of Theosophy’s, the perpendicular intersections, the “plus/minus” of this painting could refer to the spiritual insight of the unity of opposites, yin/yang, masculine/feminine etc. This balancing of duality would become a central concern of Mondrian’s work and writings. He was at this time formulating his ideas that he would later share in an essay The New Plastic in Painting. This particular painting won praise from another Dutch artist, Theo Van Doesberg who described it as "a most spiritual impression...the impression of repose: the repose of the soul/“

Van Domselaer's piano suite represented the first attempt to apply De Stijl principles to music… but what is De Stijl?

It’s interesting that these compositions specifically attracted musical response since lots of elements here, prefigure what would eventually surface in Mondrian's era-defining Boogie-Woogie work.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Mondrian found himself in neutral Holland, unable to return to Paris. He remained in Laren where he became part of a coterie of like minded artists including Van Domselaer, Van Doesburg, Van der Leck and others. Already by 1916, however, Van Domselaer was falling out of favour with Mondrian for “lapsing into melody.”! Among these artists and friends and in agreement with many of their ideas, Mondrian assimilated and processed the rich influences from his time in Paris.

LISTEN: Satie: Parade, Orchestre Nationale de l”Opèra de Monte Carlo

LISTEN: The Danceing Deacon, The 369th Infantry Regiment, “The Harlem Hellfighters,” James Reese Europe

LISTEN: W.C. Handy, Lower Basin St., Benny Carter, W.C. Handy, Dinah Shore

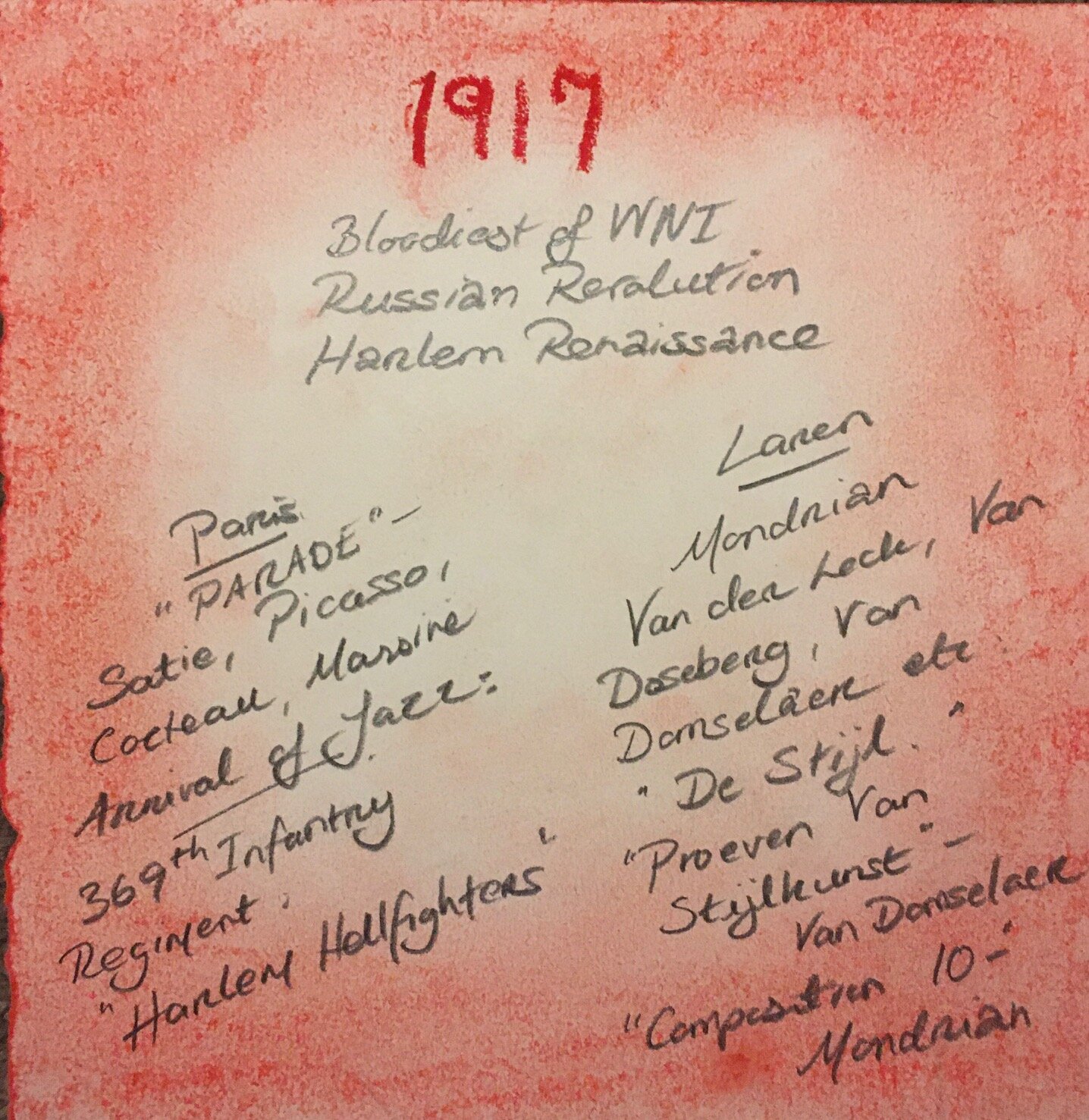

6. 1917 War, De Stijl, Parade, Surrealism, Cubism, Jazz

1917 was one of the bloodiest years of World War 1. There was also the devastation of the Russian Revolution. Against all this death and destruction, it was also a year of major musical and artistic developments.

An interdisciplinary group of Dutch artists, architects, designers and musicians including Mondrian, Theo Van Doesburg, Bart Van der Leck, Gerrit Rietveld and Van Domselaer founded the de Stjl art movement and magazine. In the first issue, Mondrian published The New Plastic in Painting, an essay that setting out the ideas of the group:

this new plastic idea will ignore the particulars of appearance, that is to say, natural form and colour. On the contrary, it should find its expression in the abstraction of form and colour, that is to say, in the straight line and the clearly defined primary colour.

De Stijl was a utopian art movement that believed that a universalism could be achieved through abstraction; form and colour were to be reduced to their essentials of vertical and horizontal lines, using only black, white and primary colours. De Stijl believed that through this stripping away, facilitated a reaching beyond the changing appearance of natural things to an immutable core of reality, a reality that was not so much a visible fact but an underlying spiritual vision.

I’ve wondered as I learned about De Stijl, about the proliferation of art movements with their magazines and manifestos at that time. I wonder if it’s to do with a growing merchant class and middle class. These new classes had fought for and found their voice, wanted to be heard and had more means to do so. They also required art to respond to their needs. Power and influence had shifted, the monarchy and nobility were no longer dominant. This must have caused a shift in art around who art was for and what it was for.

Meanwhile in Paris …..

The first Cubist musical work, Parade, a Ballet choreographed by Massine, written by Jean Cocteau, music by Eric Satie, costume and stage set by Pablo Picasso, aided by Italian futurist painter, Giacomo Balla, was presented at the Chatelet Theater on May 18, 1917. The eminent poet and critic Apollinaire wrote the program notes, searched for a new word, “sur-réalisme,” to describe it, several years ahead of when the word would come into existence.

Both the timing and subject matter of this ballet is poignant. War threatened to derail production several times of a ballet’s whose subject matter was, ironically, a bunch of circus performers in search of an audience. In the middle of a war, this ballet was raising questions of art’s relevance. How can a performance or should it draw an audience in the middle of a war? Also, with the popularity of the gramophone, camera, photography, the radio, etc… what can art do? All these brilliant new inventions were essentially displacing traditional art forms and ways of making and paying for art!

The music by Satie featured an unusual mixture of instruments, including a saxophone, a harp, xylophone, a bouteillophone (bottles filled with varying amounts of water), and various noise-making devices, including a typewriter, foghorn, and a revolver etc. This is totally consistent with what we know of Eric Satie, as a phonometrician, but in 1917 it challenged war-weary audiences nevertheless. Again Satie shows himself to be a pioneer on the uncomfortable edge of the new. His unusual instrumentation anticipates the intonarumori of the Italian Bruiteurs and noise music.

The production was denounced by one Paris newspaper as "the demolition of our national values" but Stravinsky praised it for its opposition to the "waves of impressionism, with language that is firm, clear, and without any connection with images."

Inspiring no such Parisian indignation was the arrival of a different type of music: Jazz. Jazz came to Paris in 1917, with American soldiers coming to fight in the First World War. These soldiers were accompanied by military bands, including the 369th Infantry Regiment band, comprising fifty black soldier-musicians directed by celebrated Broadway band leader, James Reese Europe. Europe was a gifted multi-instrumentalist and composer as well as a tireless champion of African American music and musicians. Europe was also the bandleader for Vernon and Irene Castle, one of the most famous dance teams of the age. So he knew how to get people dancing!

Fearless as soldiers this army band got the name the Harlem Hellfighters. Dominating in the battle field, they also dominated in the concert halls. They played one concert and their booking was extended to 8 weeks. Bringing with them dances like the foxtrot, the two-step, the one-step with new songs uncovered and freshly published by W.C. Handy like the Memphis Blues, St Louis Blues, Beale St. Blues they brought the ideals of the Harlem Renaissance to Paris. They also took something back too:

I have come from France more firmly convinced than ever that Negros should write Negro music. We have our own racial feeling and if we try to copy whites we will make bad copies ... We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others, and if we are to develop in America we must develop along our own lines. - James Europe After his return home in February 1919.

I’ll include it here because it’s an important event in Black history and Jazz that Europe was killed by one of his own musicians a year after his return. W. C. Handy wrote:

"The man who had just come through the baptism of war's fire and steel without a mark had been stabbed by one of his own musicians ... The sun was in the sky. The new day promised peace. But all the suns had gone down for Jim Europe, and Harlem didn't seem the same."

Author Jean Cocteau was enchanted by the new American sound, describing jazz as "an improvised catastrophe" and "a sonic cataclysm".

Le jazz-band est à ses yeux comme l’essence d’une simplicité, d’une pureté et d’une authenticité dont manque la musique française. Il faut se défaire de l’héritage de Claude Debussy « Assez de nuages, de vagues, d’aquariums, d’ondines et de parfums de la nuit » dit-il : il nous faut une musique sur la terre, une musique de tous les jours! - Cocteau.

7. Spanish Flu

In 1918, Mondrian contracted the Spanish flu, an epidemic that took more lives than the Great War itself. It is believed that Mondrian caught the disease from his housemate Jo Steijling (1879–1973), a primary school teacher. Mondrianʼs symptoms continued for months. But at least he survived. Beloved poet and critic of Paris, Apollinaire, was not so lucky.

8. Return to Paris, Dadaism, Les Annes Folles

When Mondrian could finally return to Paris in 1919, he was coming fully formed in terms of his artistic purpose. But it was a different Paris. It was a different world.

The question, what is art for, was asked before the War, however, after the War, it evoked very different responses. The situation is not the same, but there are parallels with what we are going through today. I think every artist is asking themselves this very questions, in a way we have never done before. Journalist Una Mullaly wrote in December just before another lockdown was announced:

Viewing Mondrian’s work, which progressed brilliantly in post-war Paris, it’s natural to reflect on the artistic booms that emerge from disaster. How are we to really know that the Roaring Twenties were not only a release of creativity and hedonism emerging from the ending of the first World War, but also the end of their pandemic? Does such a golden era of creativity await us, if the stifling forces of late-stage capitalism can get out of the way? The echoes are pronounced. Una Mullaly, out of the darkness and into the light Dec 21

I’m not sure at this point what wil happen. Perhaps it’s too early to say. But it’s definitely changing things. I’ve not been able to collaborate with my musicians on the musical aspect of this project so far. I’m probably engaging and enjoying what I’m discovering from this research more. With our pandemic, restrcitions, sickness and loss, I do relate to, and I marvel at artists’ creativity a century ago. Let’s go back to Paris at the end of the War again ……

In The Rest is Noise, Alex Ross discusses the effect of war on artists

the feelings of hyper alertness, distance and emotional coldness often overcome the survivors of horrifying events. Just as the traumatised mind erects barriers against the influx of violent sensations so do artists take refuge in unsentimental poses in order to protect the self from further damage. (Certainly there was a) shift in the European mind, a turning away from luxurious, mystical, maximalist tendencies of turn of the century art.

Among many post-war movements including Dadaism, Surrealism, Cubism and Futurism, Dadaism seems to most fit this response. Developed in reaction to World War I, the Dada movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works. The art of the movement spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound poetry, cut-up writing, and sculpture. Dadaist artists expressed their discontent toward violence, war, and nationalism.

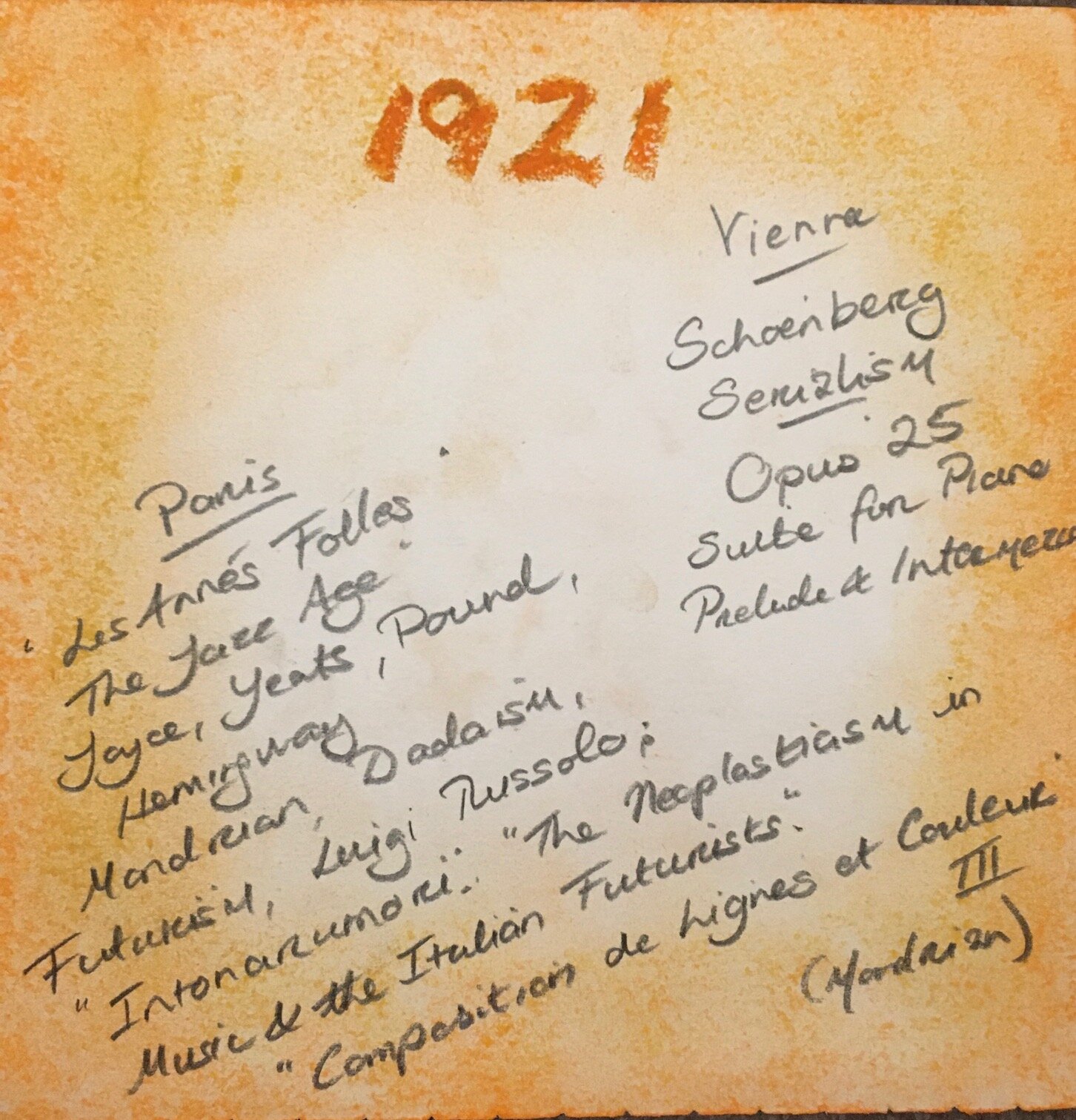

Despite the hardships and upheaval, or indeed, because of them, Paris resumed its place as the centre of the artistic firmament burning through the years of Les Années Folles, the precocious, hedonistic and reckless, Roaring Twenties, the Jazz Age.

Writers again flooded the city: Our own James Joyce was finishing Ulysses and walking the streets of Paris looking for a publisher. Ezra Pound was being sent copies of the Wasteland by T.S.Eliot for comment. Yeats and Hemingway could be found in cafes. Artists, Pablo Picasso, Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Amedeo Modigliani, Marcel Duchamp, Maurice Utrillo, Alexander Calder, Kees Van Dongen, and Alberto Giacometti all strolled the streets of the city that had again become their home. Mondrian, dabbling in Dadaism with his friend Theo Van Doesburg, would call out to each other in greeting Dadadoes! DadaPiet!

Mondrian was listening out for the Futurists. They were onto something. Mondrian wrote to Van Doesburg in 1919:

I don’t recall his name, the chief of the futurists…. In regard to form, its seems to be going in the right direction. .. I have myself discovered something of form in writing and later, I’ll try and see if it works ;..

the writing he references is Les Grands Boulevards, a stream of consciousness description of street life that has echoes of Joyce’s Ulysses:

Ra-h, na-h-h-h-h-h. Poeoeoe. Tik-nik-nik-nik. Pre R-r-r-r-r-uh-h. Huh! Pang. Su-su-su-so-ur. Boe-uh. R-r-r-r. Foeh …..a multiplicity of sounds, interpenetrating. Automobiles, buses, cars, cabs, people, lampposts, trees….. al mixed; against cafés, shops, offices, posters, display windows; a multiplicity of things. Movement and standstill: diverse motions. Movement in space and movement in time. Manifold images and manifold thoughts. - Les Grands Boulevards

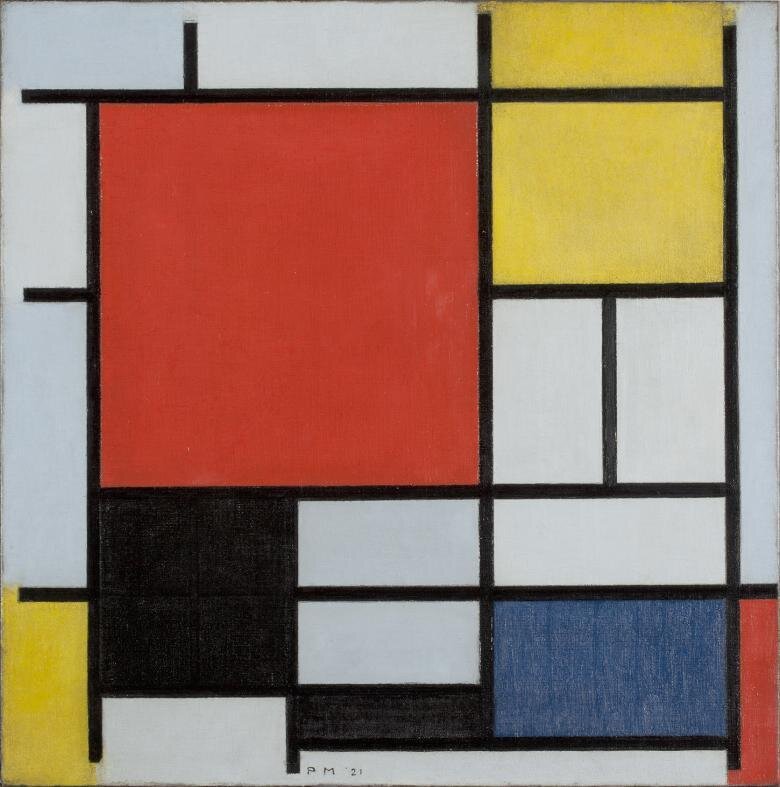

Composition with Large Red Plane, Yellow, Black, Grey and Blue 1921

9. 1921: Noise Music Versus Serialism

LISTEN: Luigi Russolo: Intonarumori, Ronzatore, Musica Futurista, The Art of Noises 1909 - 1935

LISTEN: Schoenberg: Suite fûr Klavier, Opus 25: 1, Prelude, Maurizio Pollini

Shortly after penning his praise and pinning his hope on the Futurists Mondrian got to go to a concert at the Theatre des Champs Elysses to witness 23 of the mechanical noise makers or intonarumori, bruiteurs presented by the painter and composer Luigi Russolo. The cabinets that held the music-making machines were painted red, yellow and blue which should appeal to Mondrian’s palette!

According to Luigi Russolo, (who interestingly enough, was also a member of the Theosophical Society):

Musical art today is seeking the amalgamation of the most dissonant strange and strident sounds. We are moving toward sound noise. (The Art of Noises” 1913)

Not only amid the clamour of cities but also in the once silent countryside, the machine has created so many varieties and combinations of noises that the meagreness and monotony of pure musical sound can no longer arouse emotion in the hearer.

Excited after the concert Mondrian wrote The Manifestation of Neo Plasticism in Music and the Italian Futurists Bruiteurs:

To achieve a more universal plastic the new music must dare to create a new order of sounds and non sounds (determined noise) Such a plastic is inconceivable without new technique and new instruments.

One sound is directly followed by another, which, being contrary s in real opposition. This “contrary” cannot be silence because silences its “image”. In Neo Plastic music, nonsound will be in opposition to sound as colour is opposed to noncolour in Neo-Plastic painting.

This silence should not exist in the new music. It is a voice immediately filled by the listener’s individuality. Even Schoenberg, despite his valuable contributions, fails to express purely the new spirit in music because he uses this silence (in his piece for piano). The new spirit demands that one should always establish an image unweakened by time in music or space in painting.

In 1921, Schoenberg thought he was doing pretty well! He had just written the first serialist compositions in the Prelude and Intermezzo of the Suite for Piano Opus 25. He wrote:

Ich habe etwas gefunden, das der deutschen Musik die Vorherrschaft für die nächsten hundert Jahre sichere!

In serialism, Schoenberg believed he had finally developed a system to foster musical development, something which he had regretted to sacrifice to the emancipation of dissonance in his earlier atonal explorations.

For Mondrian, it seems Schoenberg was going the way of Van Domselaer. His music was not the vision of Neo Plasticity.

Mondrian explained:

In the Neo Plastic music of the future the direct plastic means should be determined sound, the duality of sound and nonsound (noise). “Sound” is here used to signify in the auditory what is expressed by colour in painting - more or less in the sense of “tone” in music. And the word “nonsound” is chosen to signify what in Neo-Plastic painting is expressed as non-colour, that is white, black and grey.

……. probably three sounds and three nonsounds (as in painting: red, blue, yellow, white, black, grey.

Mondrian’s essays do not reference Parade, yet, I have to think that the cacophonous collision of Cubist, Surrealist and indeed Futurist influences in Parade and the achievements of the Ballet Russes with Nijinsky, must have contributed to Mondrian’s ideas on what might be possible outside of painting. We know also that he was friends with the Dutch modernist composer Danial Ruyneman. It was Ruyenman who played quite an important role in modernising music in Holland. He set up the Netherlands Society for Creative Music in 1918. This Society was absorbed into the Dutch chapter of the International Society for Contemporary Music and was also was responsible for the Dutch premiere of the ballet pantomime Le Boeuf sur le Toît by Darius Milhaud and Jean Cocteau in 1925

Mondrian quickly followed his essay on the Bruiteurs with Neo Plasticism its Realisation in Music and in Future Theatre. In it he lays out a Neo Plastic vision for future performances that would hearken today’s immersive performance:

the “hall’ would be completely different from the traditional concert hall. Neither a theatre nor a church, but a spatial construction satisfying all the demands of beauty and utility, matter and spirit. Compositions could be repeated just as films are repeated in the cinema. Whatever was lacking cold be compensated by Neo-Plastic paintings with long intermissions for the public to enjoy these paintings.

He also imagined that, “when it becomes technically possible, these paintings could also appear as projected images.” His stipulation that “the electrical sound equipment will be invisible and conveniently placed,” would certainly win him favour with conscientious performers and producers alike! And further “In the future yet another art is possible, an art situated between painting and music.”

His thoughts are precinct when we think of how today performances take place in a wide variety of settings and the influence of multimedia. I am reminded of Brian Eno’s extraordinary show, 77 Million Paintings. I wonder woudl this be Mondrian’s Neo-Plastic vision realised ?

Transcript for Podcast Part 2

Welcome to part 2 of Music for Mondrian. In part 1 I looked at some influential music and musical movements, some pioneering composers of modernism surrounding Mondrian, his work and its development. We saw how his move to Paris sparked a relationship with music that grew in parallel with his artistic development. No music sparked his passion or inspired him as much as jazz.

I’m going to delve into Jazz and Mondrian’s relationship with Jazz! In order to do that, I’m also going to look at a little more at Mondrian’s neo plasticism, as it relates to jazz and Mondrian’s love of jazz. which is so many things, a theory, a style, a technique, a philosophy a vision for the future, an art movement and ultimately Mondrian’s every day art practice and way of life. Neo plasticism is many things, as is Jazz. And I’m delighted to let you know, reflecting Mondrian’s deeper relationship with music, there will be more musical interludes on this podcast, and they will be played by my musical collaborators, Johnny Taylor and Barry Donohue on bass.

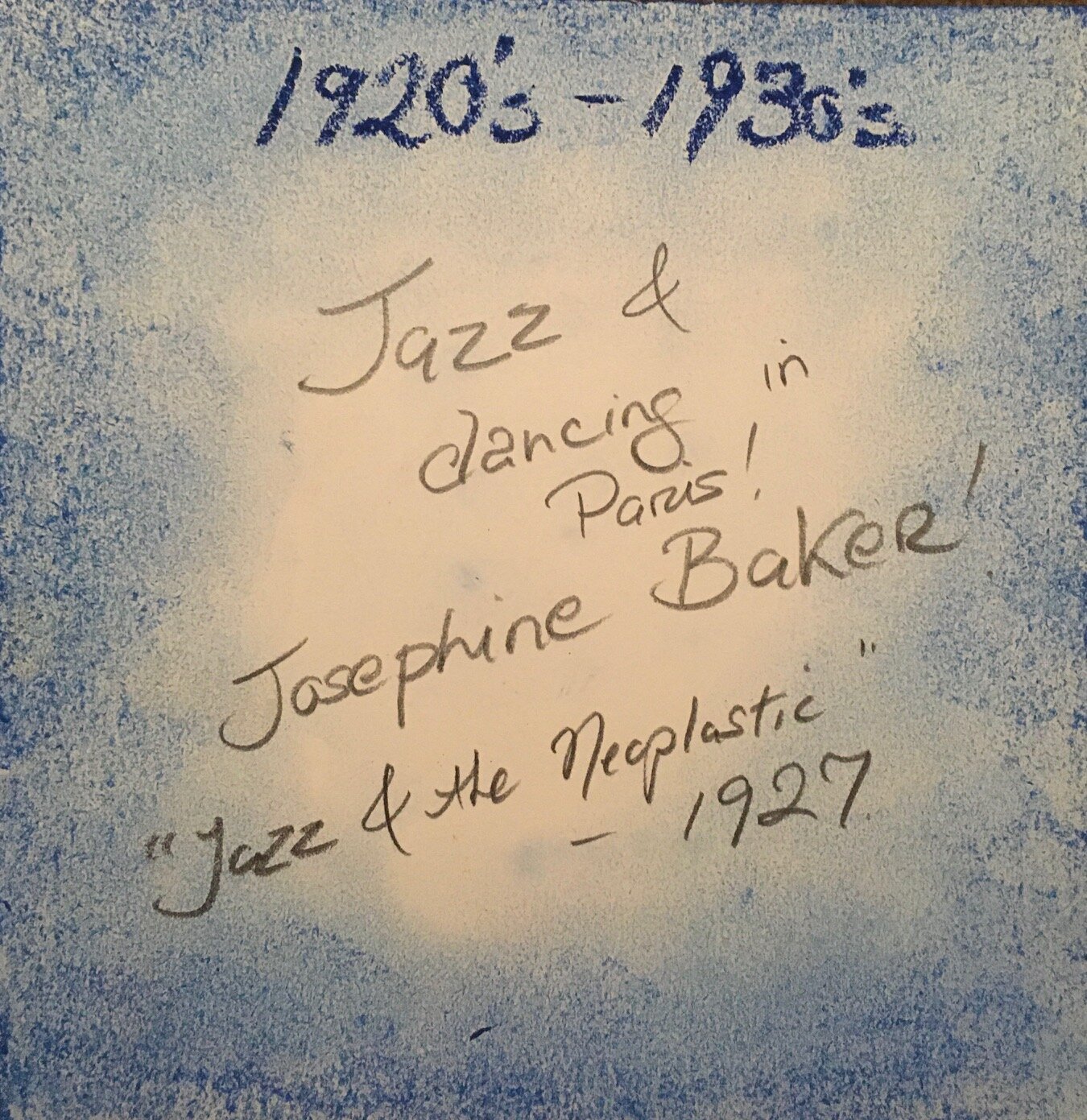

10. Jazz, Josephine, Gershwin and the City

LISTEN: James P. Johnson: Charleston

LISTEN: Josephine Baker: La Conga Blicoti

LISTEN: George Gershwin: An American in Paris, Leonard Bernstein, Colunbia Symphony Orchestra

Paris did not forget the impact of the war-time jazz bands or their dances. There was no appetite for heavy, serious music. Stravinsky too acknowledged the desire for the new “musical ideal, music spontaneous and useless, music that wishes to express nothing.” believing to have found it in the music of Jelly Roll Morton. So in 1925 Josephine Baker along with Sidney Bechet and a troupe of 25 black musicians were brought from Harlem to Paris to perform a new show called La Revue Negra at Théâtre des Champs Élysées. In this show Baker danced The Charleston and the show was a hit.

With its anticipatory syncopated rhythm, The Charleston became the anthem and embodiment of the postwar energy and movement: a solid and steady dismissal of the old for a hurried step, ahead of the beat, to embrace the new-and, with devil may care speed! The dance was named after the harbour city of Charleston, where the sound of the dockworker inspired James P. Johnson to write the tune. It appeared in the Broadway show Runnin' Wild, 1923 and ran for over a year bringing it mass appeal in dance halls across the US. The peak year for the Charleston as a dance by the public was mid-1926 to 1927. Its composer, James P. Johnson, was a founder of the stride piano idiom, a crucial figure in the transition from ragtime to jazz and a major influence on Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, and Fats Waller, who was his student

Thus in bringing the Charleston to Paris, Baker was also bringing Harlem Stride piano playing, a development from the early Jazz bands in 1917, and further validation from Europe for Black music and musicians in America.

The Théâtre des Champs Élysées continued its run of American successes with the first French performance of George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in 1926. Gershwin was entranced, by the Parisian welcome and the city itself and returned to immortalise the city in music. From his hotel balcony, looking out over the Étoile, he composed An American in Paris saying:

My purpose here is to portray the impressions of an American visitor in Paris as he strolls about the city, listens to the various street noises, and absorbs the French atmosphere.

Echoing Gershwin, and convinced that the city was the only possible epicentre of his new Neo Plastic art movement Mondrian wrote:

In the metropolis, unconsciously and in answer to the needs of the new age, there has been a liberation from form leading to the open rhythm that pervades the great city. All manner of construction, lighting and advertisements contribute. Although its rhythm is disequilibriated the metropolis gives the illusion of universal rhythm, which is strong enough to displace the old rhythm. Cathedrals, palaces and towers no longer constitute the city’s rhythm. Unconsciously the new culture is being built here. - Jazz and the Neo-Plastic

Rhythm and the City. Modernism and the City. Jazz and the City, all becoming synonyms for each other. The new unnatural ebb and flow, fits and starts of movement. The cacophony of new city sounds that roar, screech and hiss, that oppose and annihilate to create anew. Modernism pulsed in Paris. New cabarets featuring jazz, including Bricktop's, the Boeuf sur le toit and Grand Écart opened, and American dance-styles, including the one-step, the fox-trot, the Boston and the Charleston, became popular in the dance halls.

Mondrian loved to dance. He loved to go see Josephine Baker. On hearing that the Charleston might be banned in Holland, he said, “if the ban on the Charleston is enforced, it will be a reason for me to never to return.” I have found no evidence that he ever did return! He also noticed how the Charleston was “danced nervously, as it often is by Europeans, it appears hysterical. But with the negroes a Josephine Baker, it is an innate, brilliantly controlled style.”

As a sidenote, at this time in Ireland, there were protests (led by the Church) against the threat of Jazz to the cultivation of a national identity of “saints and scholars” with marches proclaiming “Down with Jazz!”

In Jazz, like the city, Mondrian began to hear a joyful expression of his Neo Plastic vision writing Jazz and the Neo Plastic writing:

Strangers amid the melody and form that surround us, jazz and neo plasticism appear as expressions of a new life. They express at once the joy and seriousness that are largely missing from our exhausted form culture.

… they are trying to break with individual form and subjective emotion…. they appear no longer as beauty but as life, realised through pure rhythm which expresses unity because it is not closed

Jazz being free of musical convention now realises an almost pure rhythm thanks to a greater intensity of sound and to it’s oppositions. Its rhythm already gives the illusion of being open unhampered by form. Neo plasticism shows rhythm free of form as universal rhythm.

Jazz music epitomised for Mondrian the primacy of rhythm and beat, as opposed to what Hans Janssen called “decorative emptiness” of the old form music. Mondrian’s whole utopian vision stemmed from this embrace of duality, of opposing forces, for it was through this opposition and only through it that a living unity, and open rhythm and pure harmony could be achieved.

Apart from the new open rhythm, in jazz Mondrian also heard some of the sound and nonsound which heralded the music of the future; “ In the jazz band which by their timber and attack are more or less opposed to traditional harmonious sounds, and which clearly demonstrate that it is possible to construct nonsound”

(Mondrian had also written a piece called Down with Traditional Harmony.)

Jazz, the City and Neo-Plasticism. It is clear from Mondrian’s paintings and writings that this trio expressed Mondrian’s Neo-Plastic vision for the future…. so it is little surprise that when he would move to NYC he would say, “I have never been so happy as I am here.”

Ultimately though, Jazz in Paris before World War II had a limited development. It was mostly staged for entertainment purposes and there did not exist the critical mass of musicians to develop it as an art form. This was all happening in New York. But before we go to New York … let me circle back a little to look at Mondrian’s vision as it’s pertinent to the discussion on jazz.

Composition with Lines and Colour III

11. His philosophy: Neo-Plasticism

The cubist work, perfect in itself, clearly could not be perfected further after its apogee. Two solutions remained: either to retreat to the naturalistic or to continue cubist plastic towards the abstract, that is become Neo-Plastic.

Jazz, above all, creates the barʼs open rhythm,ʼ wrote Mondrian, ‘It annihilates. ... This frees rhythm from form and from so much that is form without ever being recognised as such. Thus a haven is created for those who would be free of form.

Mondrian wrote - a lot. He was very passionate about communicating his vision, ideas and responses. I’ve read a lot of it! And, I understand it is as this …

Abstract artists in the main challenged traditional figurative representation of form…. Mondrian did to, but for different reasons. For Mondrian, as I understand it, form obscured what this new painting could be about. As far as he was concerned, other abstractionists were still making paintings about something — this something was not far enough away from form. Painting was still subservient to their vision in the way that it had been to form, and their vision was still too individualistic and static. Kandinsky for all his abstraction was still too personal, his painting still wound up being about expressing himself, his soul. Dali’s painting was about his dreams and subconscious. Even the cubists, for all their innovation, made painting about showing volumes and perspective…Mondrian wrote in Cubism and Neo Plastic

Once can never appreciate enough the splendid effort of Cubism which broke with the natural appearance of things and partially with limited form. Cubism’s determination of space by the exact construction of volumes is prodigious. Thus the foundation was laid upon which there could arise a plastic of pure relationships, of free rhythm, previously imprisoned by limiting form.

In short, painting was not doing anything new enough. It was still always about something, something other than itself… nature, the subconscious, about breaking down shapes,… In addition, the new art forms like photography and cinema were threatening to make it and its techniques, irrelevant and redundant.

So, it seems to me, Mondrian asked, what if painting is not about something? What could painting do if it was about nothing other then its essential self ? Is it then nothing? As an artist Mondrian was, I think asking himself the scariest questions, at the same time, some of the essential questions as artists we’re all asking ourselves these days!

Stripped back to its purest and most absolutely necessary components to exist, painting is,… lines and space. And these lines, at their most essential and differentiated, are horizontal and vertical. Mondrian wrote:

The plastic arts reveal that their essential plastic means are only line, plane surface and colour. Although they produce forms, these forms are far from being the essential plastic means of art. For art forms exist only as secondary or auxiliary plastic means and not in order to achieve particular form.

And in those lines and spaces Mondrian saw something fundamental. Relationships. Stripped back to its pure necessity, painting showed relationships. It always had done but Mondrian but they had been obscured. Mondrian laid these relationships bare.

This stripping away of superfluity and obfuscation had nothing to do with an ascetic self denial or discipline. Mondrian once protested, “but I am against discipline, I am for necessity.” Quite the contrary, Mondrian was attempting to develop an approach and movement that could be as embracing as to become universal. So Mondrian saw that the lines as much as the spaces, becomes very important for its ability to express relationships.

Mondrian realises the importance of line. The line has almost become a work of art in itself; one cannot play with it when the representation of objects perceived was all-important. The white canvas is almost solemn. Each superfluous line, each wrongly placed line, any colour placed without veneration or care, can spoil everything—that is, the spiritual.-Theo Van Doesburg

Painting had been through all the ornamentation and obfuscation of being lost to the extravagance of figurative forms and so it needed to be stripped back to show only relationships.

As Van Doesburg points out, the line, as much as the spaces, becomes very important for its ability to express relationships. Mondrian did not use rulers, but he took fastidious care with his lines. They are living things, seeming to breathe and vibrate. Some run to the end of the canvas, some stop short, suddenly, others fray into the grey. Spaces are textured and shimmer and dissolve in greys, blues and whites. This was all intentional, a way of leaving the painting seem in motion, not static and fixed but in ever present and open engagement. This liveliness and open-ness Mondrian called is dynamic equilibrium.

Equivalent and Equilibrium

Mondrian said that his intention was to establish dynamic equilibrium through equivalent relationship of the plastic means, line, plane and colour. He did not say equal. He said equivalent. This distinction is interesting. Equivalence allows for difference in commonality. In maths, sets are equivalent if they are the same in some specific way but not identical, eg. ABC - 123. I did read too that Mondrian wrote that people should not look for equality, they should look for equivalence.

It is therefore of great importance for humanity that art manifests in an exact way the constant but varying rhythm of opposition of the two principal aspects of life. The rhythm of the straight line in rectangular opposition indicates the need for equivalence of these two aspects of life: the material and spiritual, the masculine and feminine, the collective and the individual. The New Art, the New Life - The Culture of Pure Relationships (1931)

There is indeed a deep spirituality in Mondrian’s work centred around achieving unity in diversity through equivalent relationships. Equivalence allows for respect. He wrote an essay, Down with Traditional Harmony in which he redefines “Neo Plastic harmony in art is a plastic and aesthetic expression of pure unity.” This deep spirituality found expression through the plastic means of line, plane and colour. It’s like each painting might behave like a pattern or a fractal of intention, that might fractalise, and go out into the world, ripple or vibrate out into society to create rhythms of equivalence - unity in difference and peace.

Freed from form there is then just rhythm. Mondrian did not hear this rhythm in European classical music or modern music but he did hear it in jazz. It is the rhythm, polyrhythms, improvisation, swing and syncopation that sets jazz apart from other forms of music, certainly western music up to that point. You can study this rhythm, but ultimately, you have to feel it.

I often wonder, especially as I listen to Luigi Russolo’s noise music where might European music have gone if it weren’t for jazz!?! If that was the most novel point of musical development as Mondrian thought before he heard jazz!

As a jazz singer, it’s interesting to me to look at how Mondrian’s Neo Plastic vision relates to Jazz. In my experience among jazz musicians there is equivalence in relationships. Each musician brings something different and is encouraged to develop their unique voice because this difference, and articulation of uniqueness benefits and elevates the whole band and the music. Unlike say in pop music, there isn’t a hierarchy. So the drummer is as important as the singer, the bass just as important as the piano, etc. It is interesting to recall the equality in the call and response origins of jazz - a dynamic that could be compared to Mondrian’s plus-minus paintings.

In fact in thinking about the origins of jazz, its practice and performance, it seems to bee in both of these aspects, so both intrinsically and extrinsically it fits with Mondrian’s very positive beliefs that were the basis of his Neo Plasticism. That life is always right, that its obstacles are there to be opposed creatively, particularly by art, to reveal a deeper truth, a unity and beauty and provide a vision for a better future. He absolutely believed in the transformative power of creative response ..He wrote, “In life even sincere effort leads to human evolution and it is the same in art.”

He also wrote that “life shows us that its beauty resides in the fact that precisely these inevitable disequilibriated oppositions compel us to seek equivalent oppositions these alone can create real unity….. The artist composes art and life composes life. Even despite ourselves we are part of the great perfect composition of life, which when clearly seen, establishes itself in accord with the development of art.” - The True Value of Opposition in Life and Art,1934

Jazz music developed in response to oppression . It was a soul cry, from deep in the body, and deep in the body of the Black community, and the rhythm of its collective experience. It was not individualistic, the call was as important as the response to raise the collective voice and spirit of community. (As a white person?), coming to this music, I have always strongly felt the “values” of jazz, values of authenticity, respect, equality and particularly that of being part of a community, it’s the health of the whole that elevates the music. It seems to me that these values and their expressions are uniquely explicit in jazz music as an artform. Most likely because of how it developed. Jazz endlessly embraces the new, without ever disrespecting the old. From Billie Holiday's Strange Fruit, to the development of Bebop there is the triumph of eloquence over brutality and transcendence of oppression with authenticity that is joyful and free, free as Charlie Parker's horn on “Blues for Alice”

A jazz performance works equally, or perhaps better said, equivalently, horizontally and vertically. The horizontal is the relationship, your sensitivity, and attuning to your fellow musicians and their music. The vertical is your musicianship, your sensitivity and connection to the music. The paradigm could be applied to the harmony and rhythm of the music. The horizontal is melody and voice leading across chords, while the vertical is the harmonic universe of each chord, knowledge of which brings the freedom to explore and improvise rhythmically to reveal new relationships. The interplay of all these relationships bring the freedom to improvise, to play and to have a good time! This all comprises the lines and spaces of a good performance. Just as it does in Mondrian’s paintings. (i recall our own pianist Phil Ware saying there was nothing worse than listening to what he called “parallel jazz.” It might be all there in theory, but if it ain’t swinging, if there’s no relationships, nothing is happening. And let me add quickly, I’m still learning! Jazz is a lifelong condition!

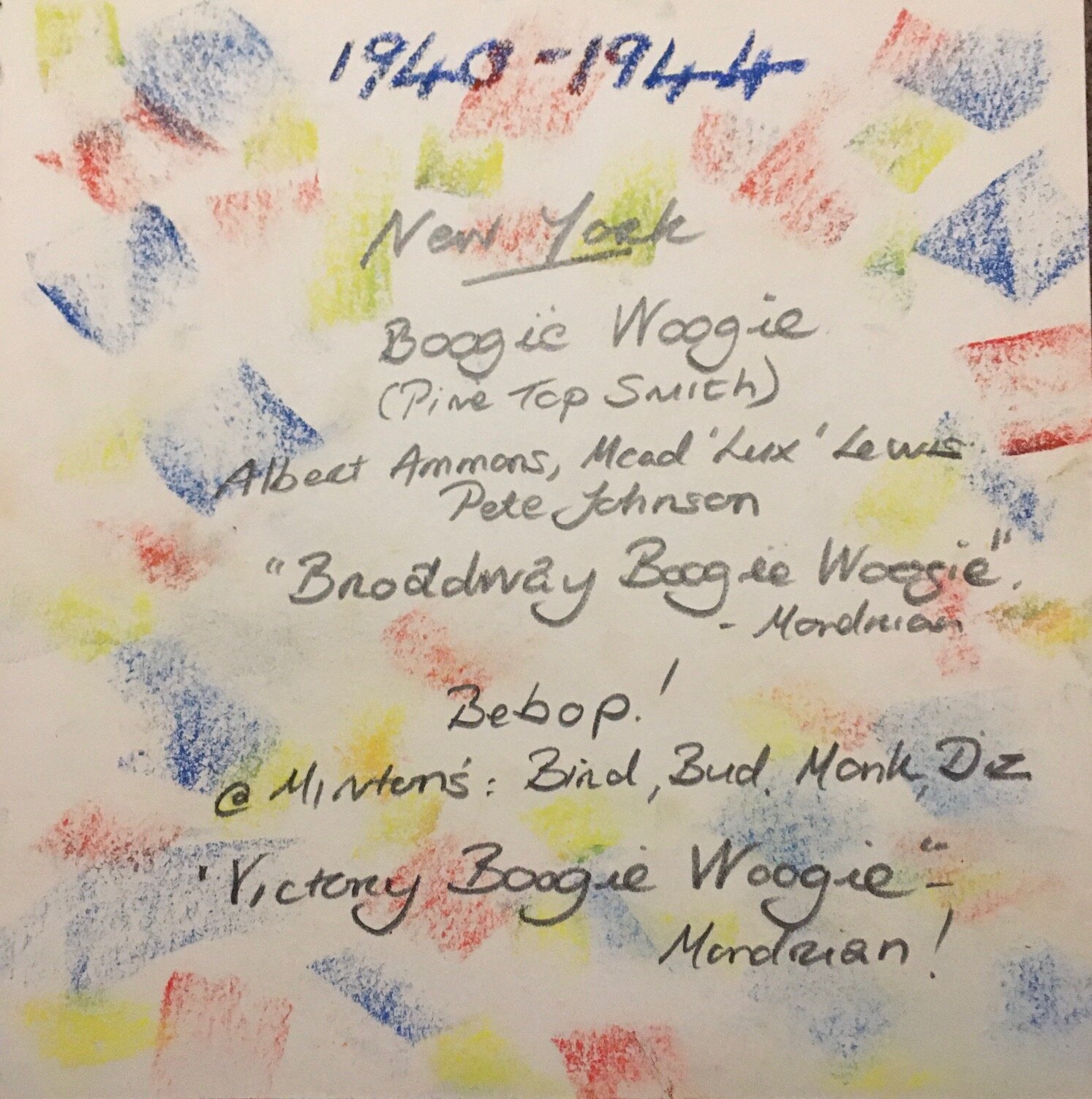

12. NYC, BOOGIE WOOGIE, BEBOP AND MONK

LISTEN: Pine Top Smith Boogie Woogie, Pinetop Smith

LISTEN: Meade “Lux” Lewis: Spirit of Boogie Woogie

LISTEN: Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson: Boogie Woogie Man

Mondrian arrived in New York in October of 1944. That first night, his friend, whom he once called his “confrère” Harry Holzman, played him Boogie Woogie. Mondrian clapped his hands and cried, “Énorme!!”

Boogie Woogie had just exploded onto the New York scene with a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1938. Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson and Meade “Lux” Lewis were discovered in Chicago by impresario of the day, John Hammond, who also discovered and launched Billie Holiday’s career at the much the same time! Lux Lewis and Ammons in fact shared a house with the originator of Boogie Woogie himself, Mr Pine Top Smith. Unfortunately Mr Smith was shot in a dancehall brawl and never made it to Carnegie Hall.

I can’t resist quoting from a report by The New Yorker on meeting Lux and Ammons after the concert at Carnegie Hall:

“They haven’t heard of Carnegie Hall, because they are primitive artists, uninterested in worldly affairs! You can’t intellectualise boogie woogie,” revealed Mr. Hammond!

Several African words like “Booga” for beat and “bogi” dance are believed to be the source of the word “boogie” confirming the African American origin in the music. The article doesn’t go into that but quotes came from the expression to “pitch a boogie” which was another name for the "house rent party."

The "House Rent Party," to pitch a boogie, was a party given by a tenant as a means of raising his rent. Crowds would gather round the boogie woogie men, the musicians, as they played and everyone get roaring drunk! "Lux” Lewis recalls how it took him two whole days to wake up after the revelry of one such party and how whenever he played his Honky Tonk Train Blues it always summoned the cops! He and Ammons would have to hide out on the window til they were gone and then they’d go right back playing - after they finished off the unemptied jugs!

Rare footage capturing Ammons and “Lux” Lewis playing together in the independent film, Dream of Boogie Woogie gives an idea of the virtuosic exuberance of their playing and how exciting attending a live performance (or a cutting session, when one tries to outdo the other) must have been! This movie also shows a young Lena Horne!

Boogie woogie playing is characterised by the Blues, because it is typically based on the same chord progression. But, while standard blues traditionally expresses a variety of emotions and with range of subtlety, there’s nothing subtle about boogie-woogie! Boogie-woogie is dance music. It is not music for talking about feelings!! It is dance music/making the rent music: the louder, the faster the better!

Pinetop's Boogie Woogie consists of instructions to dancers:

Now, when I tell you to hold yourself, don't you move a peg.

And when I tell you to get it, I want you to Boogie Woogie!

This music is a joyful triumph of rhythm over melody carried by varying patterns by the left hand with riffs, outline and augmentation by the right. And the form is free… that is, it follows a blues form, but basically a boogie-woogie musician is free to extend or curtail the form and play as long or as briefly as he likes!

I found another deliciously satiric article from a New Yorker of 1941 that I can’t resist sharing here. Unashamedly delighting in Mondrian’s eccentricities, with the aspect of a quizzically raised eyebrow behind horn-rimmed glasses, the reporter introduces Mondrian to New York as “another Paris artist who the war has expatriated here…”- Piet Mondrian, probably the only painter in the world who hasn’t drawn a curved line in twentry years.”

Continuing with bemused curiosity the reporter relates how “when war broke out, friends begged him to move to the country with them, to which he replied, he’d rather be bombed in town! And he was bombed in town; ….” It says he “likes oranges and often sucks one while he dances (to his records) but that he”is sorry records and oranges are circular!” It reports he is “delighted by his Manhattan quarters which looks out on to First Avenue where there isn’t a piece of greenery in sight, or much that is round.”

Often a critic of the serious, (though quite the culprit himself, using words like annihilation to describe the sound in a city and cutting friendship with Van Doesburg when all he wanted to do was include the diagonal line in his work!) I’m tempted to think Mondrian might have liked this new American attitude of lighthearted irreverence towards him and his work!

This impact of New York City on Mondrian, I think it best understood by the explosive change we see in his work….

It seems to me, Mondrian realised more might be going on with the lines themselves, that rather than being pure catalysts, these lines might themselves participate in and be affected by the relationships they create and their resulting equivalence. Maybe the lines themselves are changed by these relationships just as Jung said:

The meeting of two personalities is like the contact of two chemical substances, if there is any reaction, both are transformed. “ Carl Jung Modern Man in Search of a Soul (1933)

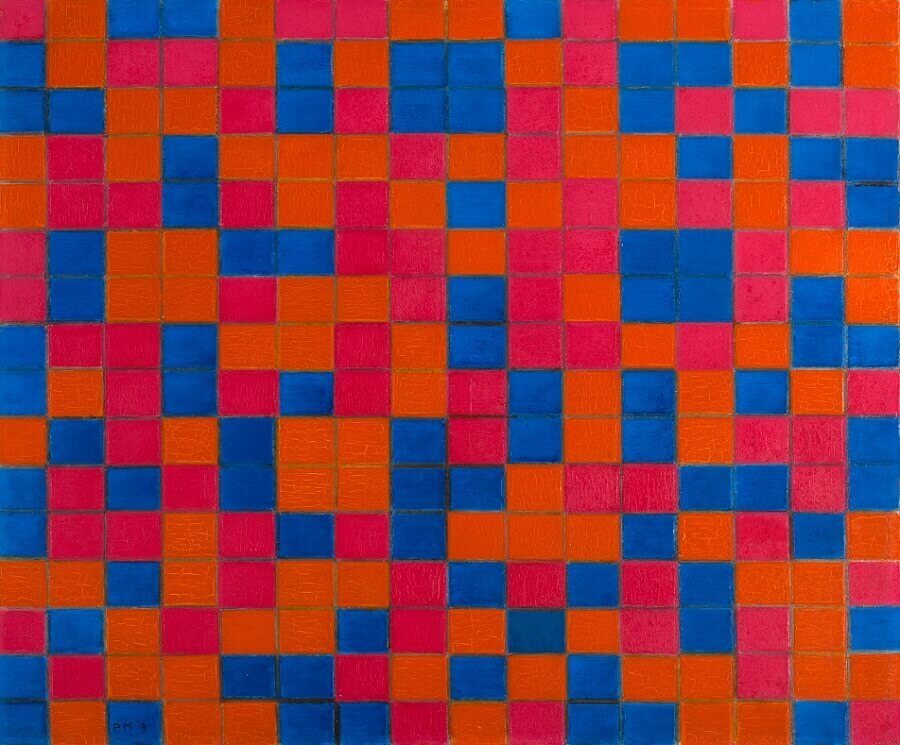

Gone are the black lines and the uniform planes of colour. This painting is dancing and joyful! It’s the colours of notes played on the boogie-woogie piano: the yellow is the repetitive figures and rhythm of the driving bass line played by the left hand overlaid by runs and flirtations in multicoloured segments by the right hand. It’s the flashing footwork of dancers in Cafe Society, on 52nd St. It’s the grid of Manhattan’s streetlights, of the City that never sleeps! It’s the sight and sound of traffic, horns bouncing off buildings, the tiny, blinking blocks of colour, like tail lights, a vital and pulsing rhythm, jumping from intersection to intersection on the streets of New York City.

I'm crazy about this City. Daylight slants like a razor cutting the buildings in half. In the top half I see looking faces and it's not easy to tell which are people, which the work of stonemasons. Below is shadow were any blasé thing takes place: clarinets and lovemaking, fists and the voices of sorrowful women. A city like this one makes me dream tall and feel in on things. Hep. It's the bright steel rocking above the shade below that does it. - Jazz by Toni Morrisson

The Carnegie Hall concert was not only a musical milestone but also a social and political one and led to engagements for Ammons, Lux and Johnston at Cafe Society, one of the few integrated clubs of NYC. Billie Holiday was also on the bill at this time but Mondrian was not fond of melody and singing, so it’s more likely on these nights, he went up to Minton’s Playhouse, in Harlem, to listen to a pianist, who had caught his ear, one who, like Mondrian had his own eccentric style of dance: Monk!

Monk was the house pianist at Minton's. He was a hard swinging player with a solid foundation in stride and runs in the style of Art Tatum. As if that wasn’t enough to recommend him, like Mondrian, though he generously acknowledged his influences, Monk was in a league of his own and one of the most original players ever. It’s small wonder then something new was going down around Monk. Those late night jams, drew like minded cats: Dizzy Gillespie, Joe Guy, Charlie Christian, Kenny Clarke, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and as they played late into the morning, a new sound was being born: Bebop!

I refer again to an article in the New Yorker for the zeitgeist of the discovery of Bebop quoting Dizzy Gillespie:

That old stuff was like Mother Goose rhymes. It was all right for its time but it was a childish time. We couldn’t really blow on our jobs — not the way we wanted to. They made us do that two beat stuff. They made us play that syrupy stuff. We began saying, man, this is getting awful sticky. We began getting together after-hours at Minton’s playhouse on 108th St.

Modern life is fast and complicated and modern music should be fast and complicated. “It was at Mintons that the word bebop came into being. Dizzy was trying to show a bass player how the last 2 notes of the phrase should sound. The bass player tried it again and again but he couldn’t get the 2 notes. Bebop! “Bebop!” Bebop!” Dizzy finally sang!

This same article introduces Monk at the time as a

sombre, scholarly, 21 year old Negro with a bebop beard, who played the piano with a sacerdotal air as if the keyboard were an altar and he an acolyte. “We liked Ravel, Stravinsky, Debussy, Prokofiev, Schoenberg, he says and maybe we were a little influenced by them.”

It’s little wonder why Mondrian was attracted to the sound of this new music. Bebop is fast and unscripted. It’s provocative and requires virtuosic technique and superior harmonic intuition. It’s characterised by fast tempi, asymmetrical phrasings, complex syncopation, advanced harmonies, intricate melodies, altered chords and chord substitutions. The role of the rhythm section is expanded with more emphasis on freedom and lead playing. Bebop was a manifestation of revolt and yet, it was also “the next logical step.” It was not developed in any in any deliberate way.

Monk was one of the most original exponents of the music. His compositions and improvisations featured dissonances and angular melodic twists, consistent with his unorthodox approach to the piano, which combined a highly percussive attack with abrupt, dramatic use of switched key releases, silences, and hesitations. His style was not universally appreciated; the poet and jazz critic Philip Larkin dismissed him as "the elephant on the keyboard." Echoes of Satie.

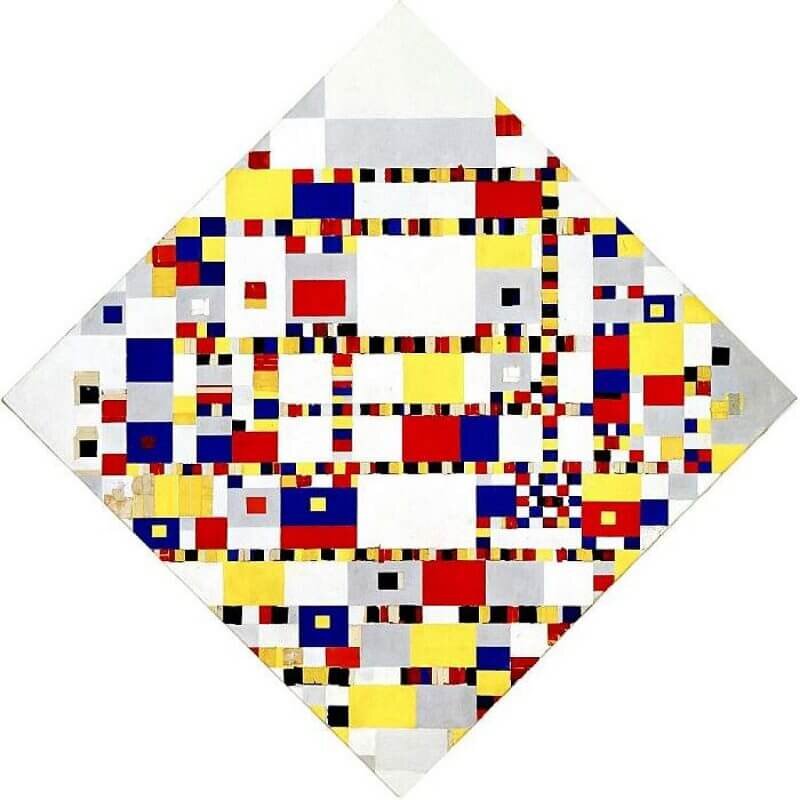

Victory Boogie Woogie

We can see why this kind of music would appeal to Mndrian…. I would argue that Victory Boogie-Woogie is the result of the influence of Bebop. The squares of colour are much more frequent, and the orderly grid present in Broadway Boogie Woogie is barely discernible. The yellow horizontal and vertical lines are dotted with more colours, and there are even more rectangles of colour. The increased complexity of this piece shows the progression of boogie woogie to be-bop, a much faster and more improvised form of jazz.

There’s something else too. The Boogie-Woogie paintings never travel. They’re much too fragile owing to Mondrian’s New York way of working with applying coloured tape onto the canvas which he moved around and around until he was eventually happy. I would say this new way of working also owes much to the influecne of jazz. It is a much more responseive and improvisatory way of workng. Just like a jazz performance, every time it’s different.

Notably in New York, Mondrian reverts to giving his painting titles. I would say this is less a return to narrative description so much as it was a literal acknowledgement of the place and music that so expressed his Neo-Plastic vision. To me it feels like in these last paintings, the rhythm and openness he had searched for and an art of pure relationships he was finding. And it was in music and of a place.

So there we will leave Mondrian listening to Monk at Minton’s and visualising how he’ll change his Victory Boogie Woogie when he goes home. It’s worth adding that of course the word bebop was barely in use before 1944…so maybe the title Victory Boogie Woogie was Mondrian’s attempt to describe what must have sounded like a hybrid music he was hearing…. maybe… Anyway there we will leave him, where, as he said, he has never been happier and in the only place in the road where modern art could flourish.

it’s been quite a trip from Mondrian’s relatively conservative beginnings to pioneering a new abstract modern art movement, surrounded by music, minimalist, classical, atonal, futurist, serialist to boogie woogie, bebop and jazz……and within that musical surround, there was Mondrian’s musical journey from detachment to interest and immersion.